Formal Analysis

Yale School of Architecture

Spring 2018 Core II

Critics Peter Eisenman with Elisa Iturbe and Orli Hakanoglu

Published Retrospecta 41

This course studies the object of architecture—canonical buildings in the history of architecture—not through the lens of reaction and nostalgia but through a filter of contemporary thought. The emphasis is on learning how to see and to think architecture by a method that can be loosely called “formal analysis.” The analyses move through history and conclude with examples of high modernism and postmodernism.

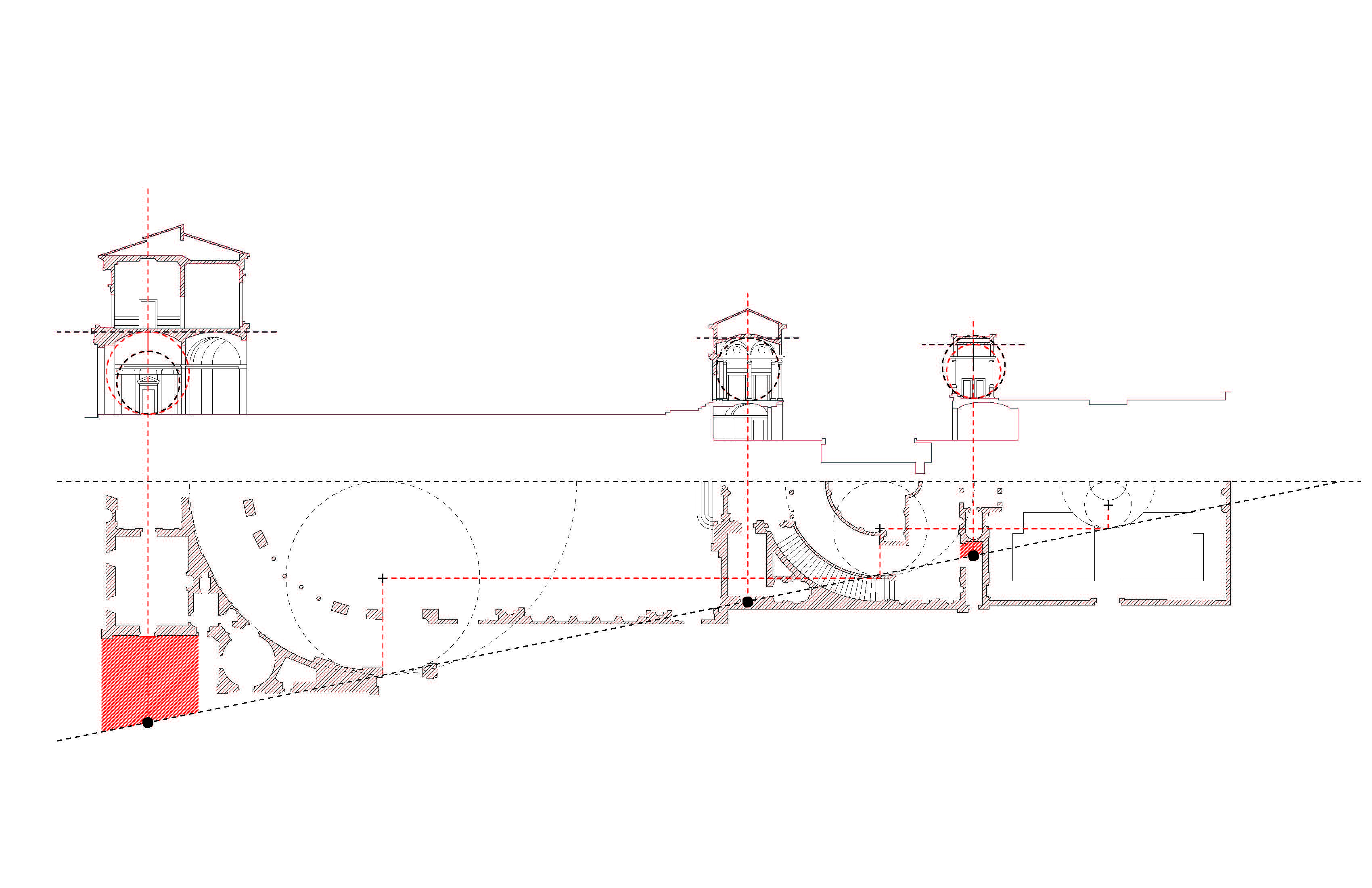

Vignola

The Villa Giulia consists of three spaces that were linked together (the Casino, the Nymphaeum and the garden) as a sequence. While these spaces, constituting of semicircles, did not constitute as “a whole”, it was an additive organization in the unification of the building, similar to the process in which it was designed and built. The sequence became a progression of scale from the casino to the garden in order to link the three experiences together. The diameter of the semicircular space dictated by the casino dictates the diameter of the nymphaeum, which also dictates the diameter of the center space in the garden. This proportional relationship within plan is also explored in section, where relationship is not as clear. Sectionally it exists as off axis: the centrifugal motion that offers a varied experience in plan also has a compression and expansion, signifying a change in function as one experiences the building. The breaking down of part to whole is thus significant, as the centrifugal motion is off axis in section

Bernini & Rainaldi

There exists a nuance of tripartite within the interior of both Miracoli and Montesanto. Miracoli emphasizes the middle bay through the double pilaster continuing past the cornice and then the pediment, signifying a vertical push. In Montesanto however exists a non-hierarchical tripartite because of the equal spacing articulated in the niches. This is also emphasized by the pilasters being broken by the existing cornice. In addition, Miracoli exists as one radius, emphasizing a central influence, whereas the existence of multiple radii in Montesanto emphasize a linear nature to the interior space.

Bramante

Bramante used both vertical and horizontal continuity to create the effect of three-dimensional quality of space in perspective. He achieves this by creating an ambiguous relationship between an element’s original function and its new meaning in space.

Within S. Maria de la Pace in particular, the continuity of the cloister is defined by full expression of the module. This creates a vertical and horizontal continuity within the cloister, allowing a complete reading alongside the underlying grid that exists within the courtyard and also beyond it, in the cloister space and walkway. This is in contrast to the courtyard of Palazzo Ducale in Urbino, where there is an absence of continuity in the courtyard. The incomplete module leads to perspectival discontinuity in the space, leading to a planar reading as opposed to part to whole.

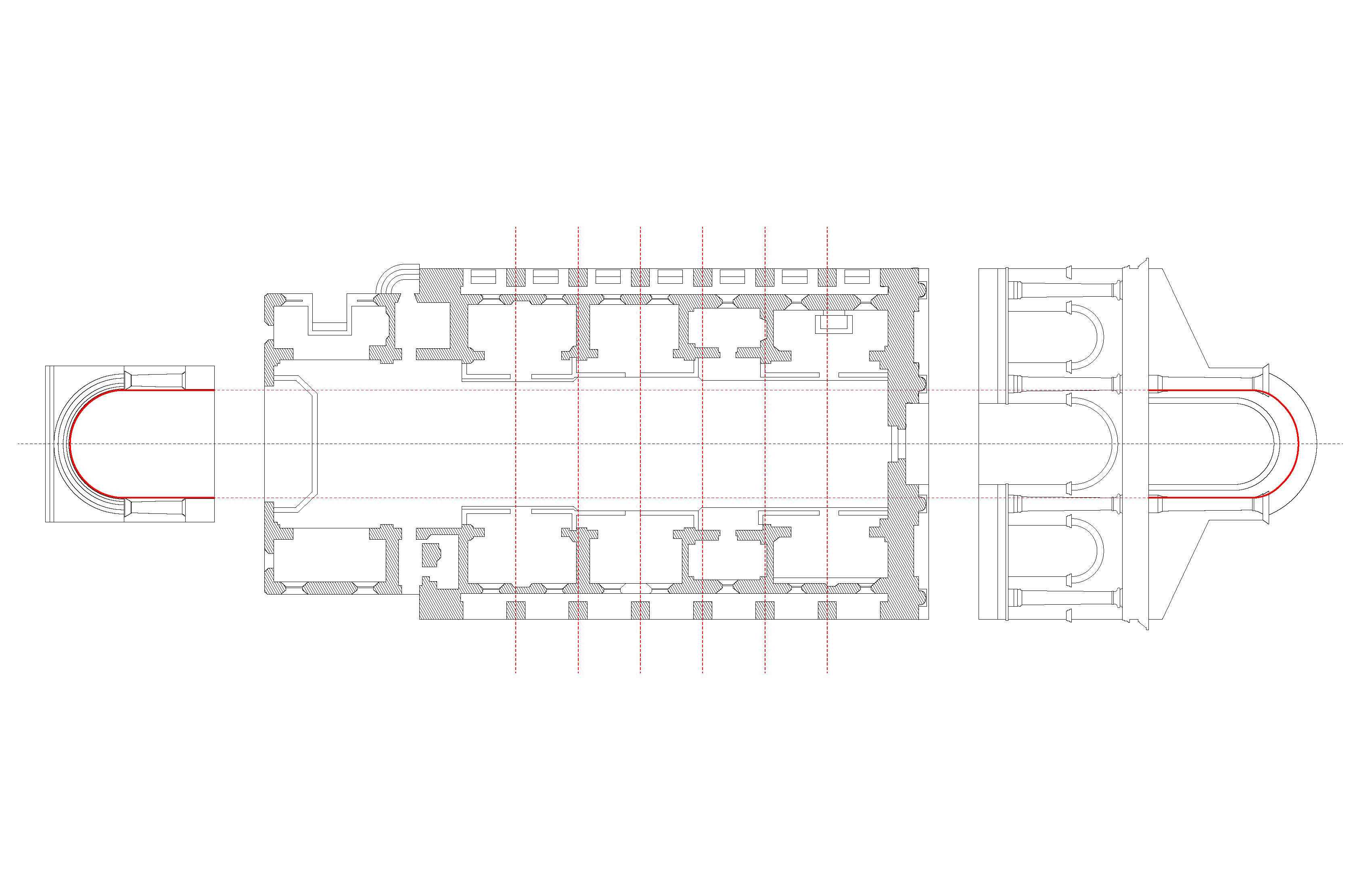

Alberti

In Alberti’s Tempio Malatestiano, there is a prominent relationship between the exterior and interior longitudinally, through the scale of the triumphal arch in the façade and the arch in the back of the church that continues through the central nave. However, the relationship between the exterior and interior laterally is not clear. There is a disjointedness and misalignment that exists between the exterior rhythmic columns and the gothic interior walls, emphasizing difficult proportions and off center windows. In a sense, the Tempio Malatestiano becomes an exterior framing an interior building.

Nolli & Piranesi

The figure ground map of Nolli represents Rome topographically as a figure ground drawing, while Piranesi’s view of ancient Rome subvert the real dimensions of the buildings and there is a scalar change. According to Tafuri, Piranesi’s interpretation shows a “truth beyond the real” through the merging of architecture with the urban continuum as opposed to the stark differentiation through positive/negative space in the Nolli map. By representing Rome through select monuments and ruins, the city becomes represented through dialectic conditions: the modern city and the ancient city, both removing the urban framework through an indefinite opening up of spaces. The Nolli map on the other hand, as an exercise in cartography is incredibly precise in scale and grounded on realism. Rome now appears as an equal reading in contrast to Rome represented through its spectacular iconic images. The drawing represents the scalar shift in Piranesi’s map of Rome where his composition of the city consists of monumental scaled architectural figures, side by side with Nolli’s mapping of the existing urban fabric. The streets on the Nolli map intersect the Piranesian figures, showing the disproportionate scale when the maps are overlaid on top of each other. In Piranesi’s map the architecture is the urban fabric while in the Nolli map the architecture exists within the urban fabric.